Sargassum is a Growing Problem. Researchers May Have a Solution

A large mass of sargassum — a type of leafy brown seaweed that floats on top of the ocean — is expected to blanket the shores of some Atlantic Coast beaches this summer, potentially wreaking havoc on local ecosystems and economies.

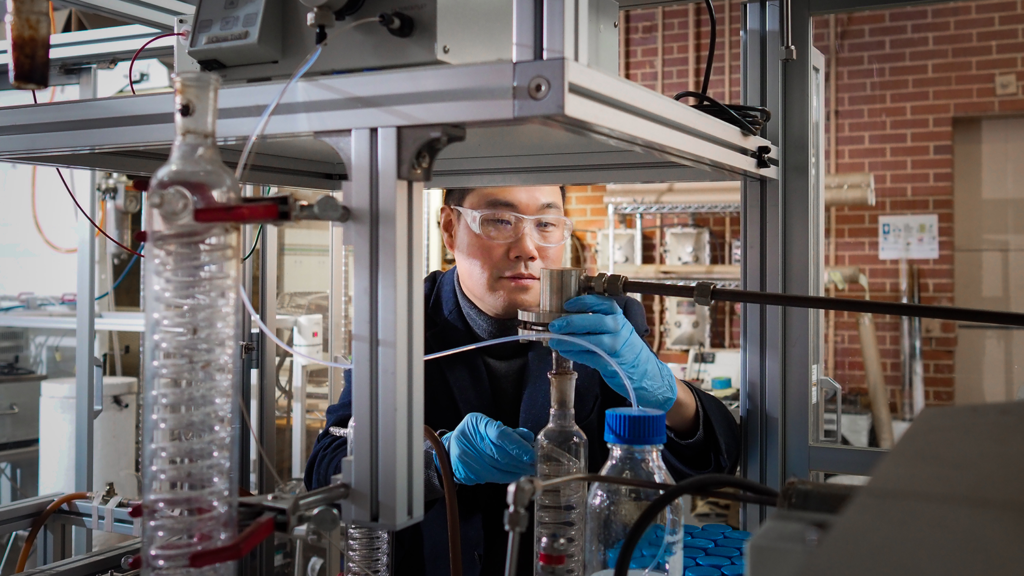

Funded with a $2.25 million grant from the Department of Energy, NC State researchers at the College of Natural Resources and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences are spearheading a project that could eventually curb these effects.

“Our project will not directly reduce sargassum blooms, but it will provide an incentive to remove it from beaches,” said lead principal investigator Sunkyu Park, a professor in the Department of Forest Biomaterials at the College of Natural Resources.

Large piles of sargassum accumulate on the shores of Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean islands every year, usually between March and October. It can not only block access to beaches and ports, but it can also negatively impact water quality.

These problems often arise when sargassum isn’t cleaned up in a timely manner. Because the seaweed begins to decompose within 24 hours, it must be processed or preserved relatively quickly. If not, it can emit an unpleasant smell that deters tourists and even discharge arsenic and other heavy metals from its flesh into groundwater.

Unfortunately, the removal of sargassum can stress local resources. In 2019, Miami-Dade County’s Department of Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces estimated an annual cost of $45 million to clean up the seaweed from just a 15-mile stretch of beaches. And more recently, the U.S. Virgin Islands requested federal assistance to collect sargassum.

For Park and his collaborators, they believe incentivizing sargassum removal for corporate industries could provide a solution. That’s why they’re working to develop a technological process that will allow them to use sargassum and wood waste for the production of sustainable aviation fuel and battery-grade graphite.

“We believe this project can generate industry interest in the potential uses of sargassum for the development of sustainable technologies, while also reducing the greenhouse gas emissions associated with aviation fuel and graphite,” Park said.

The project comes at a time when the Biden administration is calling for an increase in the production of both sustainable aviation fuel and electric vehicle battery components, including graphite, in an effort to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Both the production and use of aviation fuel and graphite generate large concentrations of greenhouse gases, which then contribute to climate change. By developing sustainable alternatives to conventional production methods, Park and his collaborators hope to reduce the emissions associated with the manufacturing of these materials.

The University of Puerto Rico and the Fearless Fund, a U.S.-based organization that designs sustainable systems for aquatic biomass production, plan to collect sargassum and wood waste between July and September of this year and then send it to collaborators at NC State and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory for processing.

Park and his collaborators plan to combine the two materials through chemical processes and then separate the mixture into a liquid and solid. They will then ferment the liquid to ethanol, which is a precursor to sustainable aviation fuel, while converting the solids to battery-grade graphite using an iron-based catalyst.

Ultimately, the project’s technology could produce up to 61,000 tons of graphite per year, which is roughly 3.4% of the current global synthetic graphite production, and up to 78 million gallons of sustainable aviation fuel per year, enough to meet 2.6% of the Biden administration’s goal of 3 billion gallons of sustainable aviation per year by 2030.

Aside from reducing the greenhouse gas emissions, the project could lead to improved harvesting approaches for sargassum and wood waste as the Fearless Fund works to identify value for these materials. This could prove especially beneficial for coastal communities as sargassum blooms are growing larger every year.

Park and his collaborators have also partnered with Birla Carbon, one of the world’s largest manufacturers and suppliers of carbon black, to assist with the development and commercialization of the project’s technology.

Co-principal investigators include Joe Sagues of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences; Meg Blanchard of the College of Education; Richard Venditti and Steve Kelley of the College of Natural Resources; and Xiaowen Chen and Mark Nimlos of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

This post was originally published in College of Natural Resources News.