The Hidden Figures of America’s National Parks

Madison Grant. John Muir. Theodore Roosevelt. These white individuals — despite having shared racist, xenophobic and imperialistic views in their writings — have long been considered figureheads of the American conservation movement.

However, Black naturalists and conservationists have also made important contributions to America’s outdoor spaces, especially national parks. These histories, unfortunately, remain largely unacknowledged and underappreciated by society, according to KangJae “Jerry” Lee, an assistant professor of parks, recreation and tourism management at NC State.

“People of color were crucial to the creation and management of national parks,” said Lee, whose research focuses on the relationship between race and ethnicity and leisure participation. “But their contributions are largely overlooked because our nation’s history is written by the powerful or dominant.”

In a recent manuscript, Lee and his colleagues examined structural patterns of injustice in the creation and history of public parks in the U.S., noting that national parks were created by wealthy and influential white people as tools to maintain white superiority.

As a result, white naturalists and conservationists — including Grant, Muir and Roosevelt — have been heroized over the decades by the white Americans who disproportionately enjoy access to national parks, while people of color have been “pushed out of history,” according to Lee.

Research shows that more than 70% of visitors to America’s national parks are white, in part because people of color face generational gaps in appreciation, skills, knowledge and experiences of these spaces due to historic discrimination.

By recognizing the contributions of people of color to national parks, society can begin to close those gaps, according to Lee. “These histories show that nature isn’t only for white people.”

In celebration of Black History Month, we’ve partnered with Lee to highlight several Black naturalists and conservationists who were crucial to the creation, management and transformation of America’s national park system. Check out the list below.

Colonel Charles Young

Charles Young was a Black military leader and conservationist who led the early development and protection of national parks in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains.

Born into slavery in 1864, Young overcame many hardships throughout his early life to become the third Black graduate from West Point and the first Black colonel in the U.S. Army.

In 1903, after being appointed captain of a segregated black company at the Presidio of San Francisco, Young received orders to take his troops, dubbed “Buffalo Soldiers,” to Sequoia National Park and General Grant National Park for the summer.

As the first Black superintendent of a national park, Young supervised payroll accounts and directed the activities of his troops, who were tasked with protecting the parks against illegal logging and poaching and building roads and trails for visitors.

Young’s troops completed a number of infrastructure projects throughout their tenure at the parks, including a wagon road to the Giant Forest, which is home to the world’s largest trees, and a road to the base of the Moro Rock.

Before departing the parks, Young initiated negotiations with private landowners surrounding the parks to sell their acreage to the government in order to ensure the preservation of its natural resources and to create additional space for future visitors.

In his report to the Secretary of the Interior, Young wrote: “A journey through this park and the Sierra Forest Reserve to Mount Whitney country will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are, with their clothing of trees, shrubs, rocks, and vines, and of their importance to the valleys below as reservoirs for storage of water for agricultural and domestic purposes. In this lies the necessity of forest preservation.”

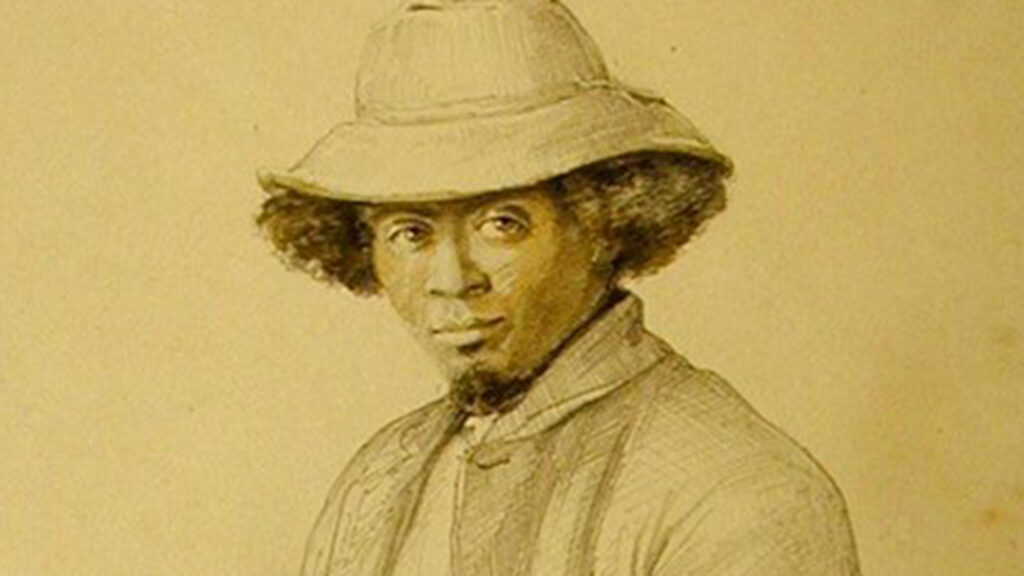

Materson and Nick Bransford

Materson “Mat” Bransford and Nicholas “Nick” Bransford were slaves who served as guides at Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, over a century before it was named a national park.

In 1838, Mat and Nick, who were unrelated but took the last name of their owner Thomas Bransford, were leased by attorney Franklin Gorin to explore the cave and provide tours.

The duo, along with fellow slave and guide Stephen Bishop, gained extensive knowledge of Mammoth Cave as they led wealthy tourists through its many passageways over the years, culminating in the discovery of features such as the 200-foot-high “Mammoth Dome.”

Throughout their time at Mammoth Cave, Mat and Nick also met a number of notable people, including poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, opera singer Jenny Lind, Grand Duke Alexis of Russia, General George Custer, Brazil Emperor Dom Pedro, among others.

Mat and Nick died in the late 1800s. Their legacy, however, lived on thanks to Mat’s son, Henry, who served as a guide at Mammoth Cave for 19 years. After his retirement, Henry’s sons, Matt and Lous Bransford, served as guides for over three decades.

During the 1920s, at the height of segregation, Matt and his wife, Zemmie, turned their house into the Bransford Summer Resort, providing accommodations for Black visitors and servants who weren’t allowed to stay at the nearby Mammoth Cave Hotel.

After selling their property to the federal government in the 1930s for the creation of a national park, Matt and Zemmie retired and relocated to Cave City, over 10 miles away. Louis retired in 1940, a year before Mammoth Cave was named America’s 26th national park.

Jerry Bransford, the great-great-grandson of Mat, became an interpretive ranger at Mammoth Cave National Park in 2002. He now regularly shares the legacy of his ancestors with visitors.

The Jones Family

For more than a century, the Jones family watched over the island of Porgy Key, protecting miles of untamed wilderness from development for future generations. Today the island is enjoyed by the millions of tourists who visit Florida’s Biscayne National Park every year.

Israel Jones, most likely born a slave in North Carolina, moved to south Florida in 1892 in search of a job. During this time, he worked on several farms and learned the skills needed to grow lime and pineapple trees. He also met his wife, Mozelle, and started a family.

By 1897, Israel had saved enough money to purchase the island of Porgy Key for $300. He then purchased Old Rhodes Key about a year later and began farming limes and pineapples. In time, the Jones family became one of the largest producers on Florida’s eastern coast.

Israel gave the farm to his sons, Arthur and Lancelot, before dying in 1932. But in 1938, as limes became less profitable, Arther and Lancelot began operating fishing and guiding tours instead. The brothers fished with many notable people, including Herbert Hoover and Richard Nixon.

By the time Arther died in 1966, Porgy Key became the target of developers who wanted to transform the Keys into a tourist destination. Lancelot, who was the region’s second-largest property owner, instead chose to sell the land to the National Park Service in 1970.

The National Park Service permitted Lancelot to live out the rest of his life in his family home on Porgy Key. In 1980, the island was incorporated into Biscayne National Park. For many years afterwards, Lancelot shared what he knew of the island with tourists.

Lancelot died in 1977 at the age of 99. In 2013, the Jones property on Porgy Key was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Biscayne National Park now recognizes the second Monday in October as Lancelot Jones Day, commemorating his life.

This post was originally published in College of Natural Resources News.