On the door of Dr. Dean Hesterberg’s office in Williams Hall is a sticker that reads, “I heart soil.”

That simple phrase sums up the driving motivation behind his more than two decades of research: discovering principles of soil science that can be used to address agricultural and environmental challenges in North Carolina and beyond.

“Soil is the basis for all life,” Hesterberg said. “It holds nutrients for crops, is the main medium through which we grow the majority of our food and is what we rely on to remove contaminants from water.”

A graduate of Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, Purdue University and University of California-Riverside, Hesterberg began working at NC State in 1993. Using mainly synchrotron x-ray technology, Hesterberg studies the fundamental mechanisms by which chemicals bind to soil at the molecular level. His ultimate goal is to bridge the gap between lab research and actual management of soil in real-world settings.

“Soils are so complicated. It’s like the ultimate puzzle to figure out. We collect an amazing chemical map. What kind of information do we get from this? That’s why I got into soil science,” he said.

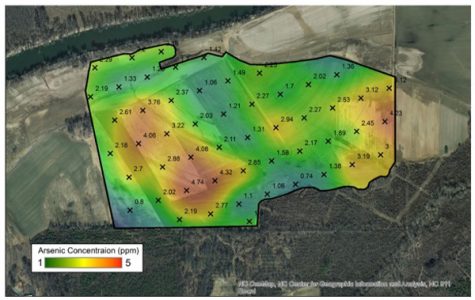

Hesterberg’s expertise has been sought in soil-related environmental challenges in North Carolina, including lead contamination at an industrial site near Concord and soil remediation management at the Marine Corps Air Station in Cherry Point, where lead, chromium, zinc, copper and other heavy metals had impacted some land areas.

After the 2008 Tennessee Valley Authority coal ash spill — one of the nation’s largest environmental disasters — Hesterberg and a team of three NC State researchers conducted a three-year study of the spill’s aftermath. When coal ash spilled into the Dan River near Eden, N.C., just prior to planting season in 2014, Hesterberg was among the research team who determined that the river’s water should be usable in crop irrigation and as drinking water for livestock animals without harm. A followup soil study continues evaluating the long-term impacts of trace elements from the spill.

“This ongoing study gives farmers peace of mind and gives us hard data,” Hesterberg said. “We’re also looking at any changes in trace elements found in actual crops. No coal ash spill is good, and our study does not address the ecology of the river, which could also be affected.”

Findings from the study should produce practical guidance to farmers, such as raising pH levels of agriculture fields to reduce the transfer of trace elements from water to crops.

Beyond spills and other acute crises impacting soil, Hesterberg said soil health is becoming increasingly more important in today’s world.

“There are a number of elements in [smartphones and other technology] that are not kind to the environment. What we try to do [through our research] is minimize the dispersal of these contaminants into our soil, water systems and air. We are also developing more effective ways to be efficient with fertilization to increase crop yields and meet the growing global food demand,” he said.

But soil scientists aren’t the only ones who contribute to healthy soil.

“Whatever soil you have control of, such as in your own yard, try to preserve it by preventing its erosion and over-fertilization,” Hesterberg said.

Hesterberg is a member of the Center for Human Health and the Environment at NC State. Learn more at chhe.research.ncsu.edu.